The dark side of 21st Century TV comedy

BoJack Horseman started off, quite deceptively, like just another animated show for adults. It’s about a man (a horse, actually) who’s stuck in the past, reliving his glory days as a sitcom star on a banal ’80s show called Horsin’ Around. BoJack is an addict, has lots of ill-advised sex, and seems depressed – classic signs of edgy 21st-Century adult animation, in line with classics of the genre like The Simpsons and Family Guy.

Like many streaming shows, BoJack Horseman’s early fans, when it first aired in 2014, were always promising it was a slow burner – it gets better, they swore, around episode seven. But even those early evangelists couldn’t grasp the gravity of what creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg had in store: over the next six seasons, it would become a heart-wrenching rumination on no less than the meaning of life, as BoJack grappled with the hollowness of worldly success, devastating loss, a pile of dire regrets, and near death.

That horse named BoJack turns out to be the face of comedy in the 21st Century. As evidenced in BBC Culture’s 100 greatest TV series critics’ poll, the last two decades have taken the TV comedy on a careening turn toward the dark. BoJack Horseman, Fleabag, Catastrophe, Veep, and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend are among the comedies that have left the traditional sitcom form of the past – think Cheers, Coupling – in the dust. At least when it comes to shows in English – a definite bias in the poll – TV comedy is not just funny these days. The laughs come along with much higher emotional stakes, often juxtaposed with grief, shame, addiction, corruption, mental illness, and existential questions about the very meaning of life.

In Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s 2016 comedy Fleabag, the eponymous heroine works through her unaddressed grief (Credit: BBC)

As TV viewing options have multiplied exponentially in the age of streaming, we have come to take the medium far more seriously, and that includes comedy. That change has allowed comedies to stand alongside dramas in terms of prestige, as evidenced by their frequent appearances in the top 100. (By comparison, BBC Culture’s 100 greatest films of the 21st Century poll was dominated by dramas.) The great TV comedy of the 21st Century toggles effortlessly between highs and lows, laughter and tears, insights and gut punches. This makes it far closer to our real lives, which, of course, aren’t trying to fit themselves into an awards-show category. The ridiculous is always mixing with the serious. We don’t get to choose.

It makes sense that this evolution took place recently. Twentieth-century TV comedy was more straightforward – oh, the wacky misadventures of the Fawlty Towers hotel staff and The Golden Girls – and didn’t evolve much between the medium’s advent in the 1940s and the 1990s. Because television was advertiser-driven, network executives were notoriously nervous about offending or upsetting viewers, which meant most programming was aimed at pleasing “everyone” – a recipe for stifling creativity. Programming was constantly audience-tested, often foregoing creativity, surprise, or even mild discomfort in service of a larger message. (Some audience testing literally had viewers turning dials during every second of a programme to indicate whether they liked or disliked what was happening on the screen.)

TV comedy became, in the 21st Century, a space to work out the contradictions of the world

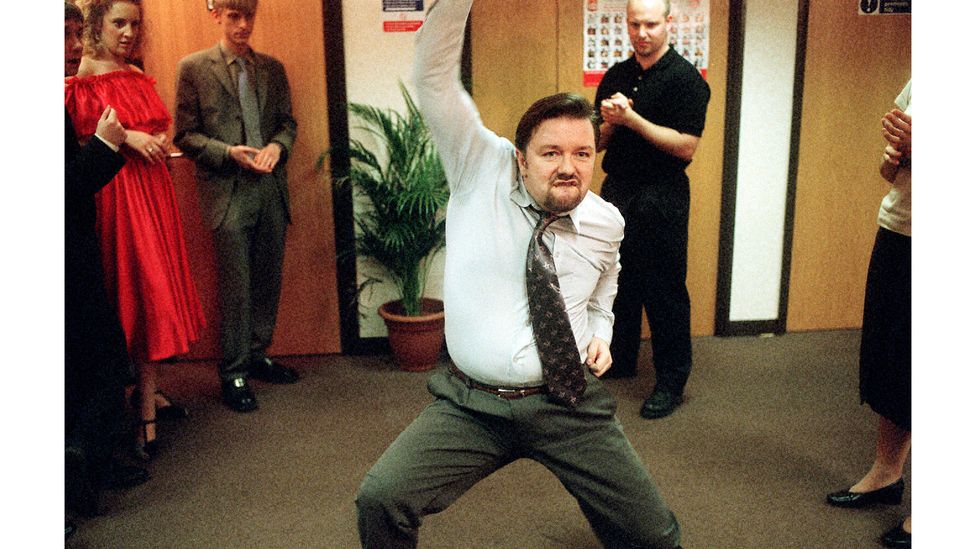

But that broke down with the new millennium. The explosion of cable programming emphasised quality, innovation, and cinematic techniques, leading the genre away from the traditional strictures of soundstage-and-laugh-track situation comedies. The increasingly crowded landscape – that began in the early 2000s as cable networks began producing original programming alongside broadcast networks – demanded shows that could make a strong impression, leading first to an emphasis on the cringeworthy. A relative of slapstick, this was an edgier approach but still in the realms of recognisable, pure comedy. Its awkwardness was often accentuated by “realistic” techniques like handheld cameras and the faux-documentary form – think Curb Your Enthusiasm and both versions of The Office. That opened the door to portraying even more discomfort as the new century went on. “Unlikable” or antihero protagonists became more common in both comedy and drama, from Larry David and David Brent to Tony Soprano and Dexter.

In the early 2000s, shows such as The Office and Curb Your Enthusiasm opened the door to portraying more discomfort in comedy (Credit: BBC)

With the rise of streaming came many more kinds of freedom: genre was less important because timeslots were obsolete; no longer were comedies marched into 30-minute blocks and strung together, nor were dramas forced into hour-long slots later at night at the more “serious” time of the evening. Programme and season lengths could vary outside of network schedules. Studio audiences and laugh tracks were long gone, a trend that began with network sitcoms like 30 Rock but was hastened by bigger streaming budgets. And standing out became preferable to fitting in, given that streaming’s infinite capacity for programming made for an overwhelming array of choices.

‘Balm for uncertain times’

Catastrophic world events likely played a part in driving comedy to the dark side. The terror attacks of 11 September 2001 were just the beginning of a steady erosion of the illusions of security and assured progress that had been a hallmark of life in the Western world in the 1980s and ’90s. From continued fears of terrorism, war, financial market meltdowns, and mass shootings, to political polarisation and the Covid-19 pandemic, the last two decades have marked a loss of innocence for many of the Westerners who created the bulk of the English-language shows on the list. Dramas had been trending darker and more complex before 9/11 with the phenomenal success of The Sopranos, which premiered in 1999. And plenty of programmes before and after 9/11 were blurring the lines between comedy and drama, thanks, most likely, to the creative freedom offered first by cable, and then streaming. But there’s something more bracing about finding the deepest and darkest of moments infiltrating comedies. Where dark comedy had been a recognisable genre in film and theatre for decades, television had traditionally shunned experimentation. Thus TV comedy became, in the 21st Century, a space to work out the contradictions of the world, recognising that even in our highest moments, life can kick us in the gut – and, crucially, that even at our saddest we can laugh.

For a stark example of how the form has evolved, take the recent international sensation Ted Lasso, whose broad premise would have easily translated to a classic sitcom of previous eras: a simple, folksy American football coach (played by the show’s co-creator, Jason Sudeikis), is transplanted to the UK and tasked with coaching an English football team – a sport that he doesn’t understand, in a totally different culture where he doesn’t fit in. It’s a classic fish-out-of-water scenario that has shown up throughout TV history, from Green Acres in the ’60s to 3rd Rock from the Sun in the ’90s. But as a phenomenon of the 21st Century, the series transformed into something else entirely by its second season: an exploration of the pitfalls of toxic masculinity, and the redemptive powers of vulnerability, honesty, and appreciation of fellow humans. One that is still, at times, very, very funny. Ted’s life might have more difficulties than those of his counterparts from the last century, but the show’s outlook is – at least after two seasons – unabashedly optimistic.

International sensation Ted Lasso used a classic fish-out-of-water scenario to explore the pitfalls of toxic masculinity (Credit: Apple TV+)

The dark comedies that made BBC Culture’s top 100 might not be quite so idealistic, but most of them come out on the side of measured optimism. The eponymous main character in Fleabag works through her grief, while Rebecca in Crazy Ex-Girlfriend learns to manage her borderline personality disorder. They survive some serious difficulties and earn their happy-ish endings – which often take the form of coming to terms with a trauma and moving forward a wiser person. This makes these series the perfect balm for uncertain times: they aren’t trying to persuade us that everything is sunny – they’re addressing the messiness of the real world, a messiness that has only become more pronounced in the late 2010s and into the 2020s.

The collapsing of genres

Of course, a few of the 21st Century’s great comedies are pitch black, without a crack to let in the light: Veep ended with a deadly cynical condemnation of US politics, and Succession has yet to reveal a shred of optimism about the Roy family, the filthy rich American media dynasty at its centre. The critical acclaim and cultish frenzy surrounding the current season of Succession underlines the chord it’s striking with audiences, with its portrayal of the greed, incompetence and impunity of the super-rich who run billion-dollar multi-media empires. To the characters within the show, the power shifts and desperate antics are dramatic; to us, the audience, they are absurd comedy.

The pitch-black Succession, which portrays the absurdity of the super-rich, has struck a chord with audiences (Credit: HBO)

It’s hard to categorise Succession at all, in fact. It’s an hour-long programme with plenty of dramatic twists and turns; it’s self-consciously Shakespearean; and the 2021 Emmys called it a drama. But it provides laugh-out-loud moments in every episode. There’s the Laurel and Hardyesque comedy duo of son-in-law Tom and Cousin Greg. There’s ambitious son Kendall’s cringe-comedy-classic rap about how great his dad, the family patriarch, is. There’s even the tiny detail of the fake headlines blaring on the Roy family’s Fox-like news channel, ATN, such as: “Gender Fluid Illegals May Be Entering the Country ‘Twice’.” The only word we currently have to describe Succession is the portmanteau “dramedy”, which has historically inferred a light drama, like an Ally McBeal or a Marvelous Mrs Maisel, rather than the blackest of comedies.

BoJack Horseman serves as a prime example of how comedy can come closer to answering that biggest of questions than any prestige drama has in its much-more-hyped finale

All of the dark-tinged comedies cited in the BBC Culture top 100 are in English, and only one non-English comedy made the list at all: France’s Call My Agent! Meanwhile, several global dramas were ranked – The Bridge, Borgen, Money Heist, and others – suggesting that comedy is more difficult to translate in general, and dark comedy, with its subtleties, even more so. This has been borne out even in past eras: the wordplay and misanthropy of American 1990s sensation Seinfeld, a clear forerunner of today’s dark comedies, was notoriously challenging for translators and Seinfeld has long lagged behind the sunnier and simpler Friends with international audiences. That said, plenty of comedies beyond the English-speaking world have recently been blurring genres as well: Japan’s Hibana: Spark uses its inherently comedic set-up – two comedians working on material together – to get a bit existential. South Korea’s One More Time is a soapy rom-com about a musician stuck in a time loop. France’s A Very Secret Service spoofs the spy genre, and Sweden’s Fallet sends up Nordic noir. These don’t rival Succession in darkness, but it seems likely there will be further international genre-blending as streaming enables worldwide audiences to access shows from any country.

Only one non-English language comedy, France’s office-based sitcom, Call My Agent! made BBC Culture’s 100 greatest series of the 21st Century (Credit: Netflix)

And, of course, there are plenty of exceptions to comedy’s shift toward darkness in the 21st Century. 30 Rock had a cynical, satirical edge, but was still, at heart, a traditional workplace sitcom – and one packed with more jokes per second than perhaps any show in history. Parks and Recreation offered a downright sunny view of local politics for the Obama Era. And Schitt’s Creek at first struck a sneering pose – look at these obnoxious formerly rich people forced to live in the middle of nowhere – then defied that image at every turn to create a utopic vision of small-town life that accepted everyone.

The real question isn’t whether the darkness or the light will win in comedy as the 21st Century goes on. BoJack Horseman serves as a prime example among many of how real, pure comedy – silly, punny, zany, animated comedy – can morph into a delicate meditation on the meaning of life… and come closer to answering that biggest of questions than any prestige drama has in its much-more-hyped finale. In the show’s final scene (spoilers ahead), BoJack, out of prison for the day on a pass to attend a wedding, sits on a roof with his friend Diane, the closest he’s come to finding a soulmate. He tells her a bit about life in prison, then he shrugs. “Well, what are you going to do?” he says. “Life’s a bitch and then you die, right?”

“Sometimes,” she says. “Sometimes life’s a bitch and then you keep living.” Pause. “But it’s a nice night, huh?”

“Yeah,” he says. “This is nice.” The episode title is Nice While It Lasted.

It begs the overdue question: when will the distinction between comedy and drama become moot? When will we be ready to admit that life is funny and sad, beautiful and tragic, and that the best of any art form reflects it all? Even, and perhaps especially, television.