When Bong Joon-ho won best picture for Parasite at the 2020 Oscars, his acceptance speech included a message to Western audiences. “Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films,” he told filmgoers who may historically have avoided non-English language movies – or worse yet, waited for their inevitable American remakes. The director didn’t have to wait long for signs his wish could be coming true.

Unless you’ve been living on a remote, internet-less island for the last few months, cut off from the world while you compete in a variety of deadly games for a cash prize, you’ll be aware of Squid Game. It’s a show that’s pierced the zeitgeist like a needle through a honeycomb wafer – with an estimated audience of more than 140m worldwide, it became Netflix’s most-viewed show of all time. If you were at a Halloween party in October, you may well have seen guests decked out in the show’s trademark blood-splattered green tracksuits. If you’re a teacher at a UK school, you might even have had to break up playground games inspired by the series, despite its 15 rating.

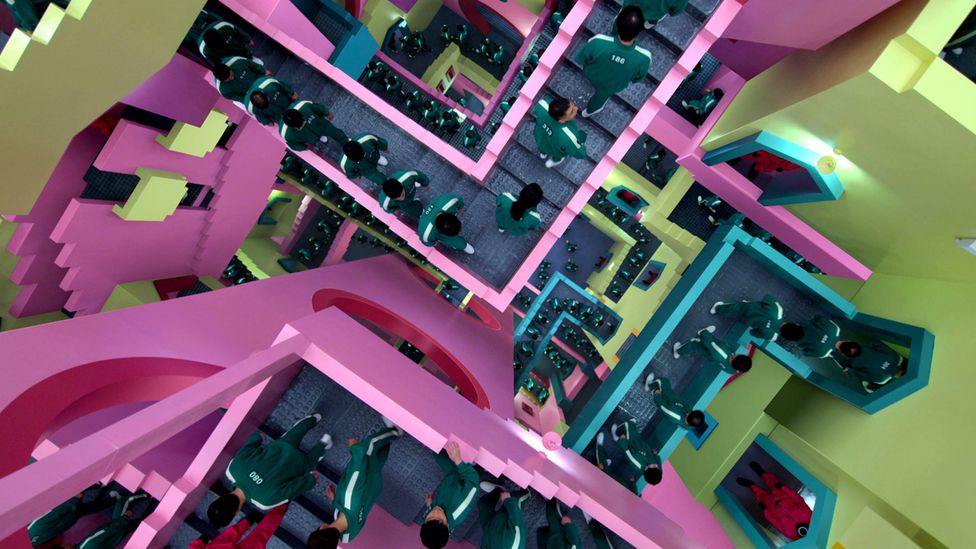

Squid Game’s reach in global pop culture is unprecedented for a non-English language show (Credit: Netflix)

From Seoul to Surrey, Squid Game’s tentacle-like reach around the planet has been unprecedented. In the last few years, there have been plenty of word-of-mouth small screen smashes that rose to become pop culture events: crime documentary series Tiger King sparked endless Zoom debates and theorising between friends during the first lockdown in 2020, for example. But not since Stranger Things or Game of Thrones has a show had this kind of pop cultural footprint.

What’s remarkable about Squid Game’s place among shows of that enormous popularity is that to get there, it had to hurdle the 1in-high wall that Bong spoke about. Tens of millions in the UK are estimated to have watched Squid Game, despite its English-language subtitles (a dubbed version is also available, but sources familiar with the series tell BBC Culture that UK audiences are largely consuming episodes with subtitles, in line with creator Hwang Dong-hyuk’s wishes).

Squid Game has achieved global mainstream visibility in a way that arguably no other non-English language film or TV show has ever managed

Non-English language movies like Parasite, Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, French romance Amélie and 2000’s Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon have all won Western acclaim and awards before (not a marker by which they should be judged: these are all astonishing works of art, with or without Western approval). But Squid Game has achieved global mainstream visibility in a way that arguably no other non-English language film or TV show has ever managed.

Which leaves a few questions. What was it about Squid Game that shattered mainstream Western hesitancy towards non-English language content in 2021? And what does its popularity mean for film and television in 2022? Is Squid Game a one-off pandemic pop culture anomaly – or the beginning of a new age of non-English language film and TV ascendency around the world?

No more cultural gatekeeping

When Seattle-based cultural commentator David Chen was growing up, “the only way to watch something like Squid Game would be through very sketchy websites or DVD shops,” he laughs. “That’s no longer the case. It’s now mass-market entertainment.” The host of respected entertainment podcasts The Filmcast and Culturally Relevant, Chen makes a good point. A decade or two ago, a series like Squid Game just wouldn’t have been accessible enough to mainstream Western audiences to enjoy the type of success it has on Netflix in 2021.

Before the advent of streaming services, most TV channels took few chances with non-English language shows. Put it this way: if The Wire, an exciting English-language drama now widely recognised as the best show of the 21st Century, struggled to get a look-in with many broadcasters, it’s unlikely there’d have been a spot for a blood-soaked, anti-capitalist Korean-language thriller series. It might have been made available as a DVD boxset in the early-to-mid ’00s as binge-watch culture took hold, but few shows made the leap from word-of-mouth boxset buzz to breakout smash status.

Our increasing use of text on phones has overcome resistance to subtitles and helped non-English language films like Parasite (pictured) to achieve global success (Credit: Alamy)

The lack of accessibility for non-English language titles back then was predicated on a suspicion among entertainment industry gatekeepers that audiences didn’t want subtitled content. “[Studios and distributors] claimed that people don’t like to read subtitles because it’s tiring or distracting on screen, but we read text all day long on our phones and in every other aspect of our lives, so I’ve always found it funny,” says Darcy Paquet, the Seoul-based author and film critic who translated Parasite into English subtitles for its international release. For years, subtitles had “an image problem – an association with something people imagine as being convoluted or difficult to watch”, he says.

Quietly, Netflix has been cultivating the exact circumstances on the platform for a global phenomenon like Squid Game to emerge

Squid Game’s success has shown that perception of subtitles to be wrong – or at the very least incredibly outdated. It’s also eroded the kind of cultural gatekeeping that enforced it in the first place. In traditional TV, there’s a limit of 24 hours a day of broadcast space that can be filled. On the servers of streaming giants like Netflix, there’s infinite space, meaning the Californian company and their rivals have thought nothing of commissioning shows in a range of different international markets, and then commissioning subtitles or dubbing for them in a variety of languages so that they are accessible to Netflix viewers across the world. Since launching in South Korea in 2016, Netflix have created 80 shows using Korean talent and creators – all of which can be watched with different subtitles or dubbing tracks from anywhere in the world, ready to be fed into viewer’s suggested shows and movies by its algorithm.

“The exciting thing for me would be if the next Stranger Things came from outside America,” the company’s chief content officer Ted Sarandos said in 2018. “Right now, historically, nothing of that scale has ever come from anywhere but Hollywood.” Clearly, that wasn’t just talk. Quietly, the company has been cultivating the exact circumstances on the platform for a global phenomenon like Squid Game to emerge, through making projects like Spain’s Money Heist and Germany’s Dark, then equipping them with all the tools to be discovered outside of those markets.

Money Heist (La Casa de Papel) was initially intended as a limited series, but was eventually extended to three seasons (Credit: Alamy)

“They really have put a lot of work into repackaging shows from other countries in a way that makes them extremely accessible to other audiences,” says Chen, who points out that Squid Game represents a culmination of these efforts. Money Heist, Dark, Spanish school drama Elite and France’s Lupin all walked so Squid Game could run, to put it another way.

Now, with Squid Game having proved that “stories don’t need to be told in English to be hits in English-speaking countries”, as Chen puts it, some industry experts are expecting an acceleration of investment in other countries from Netflix’s streaming rivals, and more marketing space given to non-English language titles than they would have received pre-Squid Game. Apple TV+, for example, has recently been promoting a new South Korean production titled Dr Brain (starring Parasite’s Lee Sun-kyun) to UK audiences with regular trailers and posters both across their social media and on the platform itself, preceding other shows and movies. “Six months ago, they might not have advertised it with the same ferocity,” one source tells BBC Culture. “Post-Squid Game is a whole other ball game.”

More South Korean content

The most obvious likely effect of Squid Game’s success is more South Korean content being fast-tracked on to screens around the world. There certainly seems to be an appetite for it: in late October, an article on The Guardian full of suggestions of K-dramas to watch if you enjoyed Squid Game was one of the top 10 most-read articles on the site, up there with whistleblower reports about Facebook’s internal practices and rumours of another impending coronavirus UK lockdown.

“People are discovering Korean content to a degree like never before,” says Paquet, noting that this “slow-building process” began two decades ago with films like Park Chan-Wook’s cult beloved Oldboy. “There were movies which did [manage to] connect with a certain number of people abroad. This last year or two, though, feels like a big leap ahead, with more almost certain to follow.” One source at a major streaming service backs up that theory. Interviewed under the condition of anonymity, they suggest to BBC Culture that with Hollywood film and TV productions still in catch-up mode following the pandemic shutdown, streamers may well begin licensing other existing South Korean shows to both capitalise on Squid Game’s success and keep their platforms packed with new content. “Everyone is wondering what the next Squid Game is, if they can make their own by investing in South Korean creators and until then, how they might be able to bridge the gap in the short term by buying in existing shows that aren’t already available [in Western markets],” they explain. “This was already happening of course but after Squid Game, [there’s] a lot more urgency.”

Already South Korean shows are being given more visibility on platforms. In November, Yeon Sang-ho’s violent fantasy series Hellbound enjoyed a marketing push that sought to capitalise on Squid Game’s success, displayed prominently in users’ libraries in a way that you suspect might not have been the case had Hwang Dong-hyuk’s show not enjoyed such massive success. Hellbound subsequently overtook Squid Game as Netflix’s most-watched show for that month, topping charts in 80 different countries within 24 hours of premiering.

The 2016 South Korean action horror film Train to Busan is getting a controversial US remake called Last Train to New York (Credit: Alamy)

South Korean film and TV was on the rise long before Seong Gi-hun, Cho Sang-woo and co donned their green tracksuits for the first time. From Parasite to Hellbound creator Yeon Sang-ho’s zombie horror Train to Busan, which has proved a word-of-mouth sleeper hit with Western audiences since its release in 2016, spawning a sequel in 2020 and an upcoming US remake, South Korean cinema has been striking a chord globally with increasing frequency over the last five years. Yeon told Time magazine in a recent interview that “Korean content gradually won the trust of the global audience in the past 10 to about 15 years… It might seem sudden, but I believe that many film and drama creators were able to gradually accumulate credibility in the global market with high-quality content, and I feel like that has led to this explosive interest.”

Lee Chang-dong’s psychological thriller Burning became the first Korean film to make it to the final nine-film shortlist for best international feature film at the Academy Awards in 2019 before Parasite swept all before it a year later by winning in the main best picture category. Since then, Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari – technically a US movie but created by South Korean talent and about the immigrant experience of a South Korean family – has also enjoyed Western awards recognition. The latest iteration of the London Korean Film Festival, meanwhile, recently attracted record crowds for its programme of 60 past and upcoming movies from across the region (“I’m especially excited for people to see Ryoo Seung-wan’s Escape from Mogadishu. It’s a film that really bowls you over with its scale,” beams Paquet).

In 2020, BTS became the fastest act to accumulate five US number-one singles since Michael Jackson (Credit: Alamy)

Paquet describes the boom in South Korean cinema abroad as part of a wider cultural rejuvenation. For decades, as the New York Times’ Choe Sang-Hun recently wrote, “the country’s reputation was defined by its cars and cellphones from companies like Hyundai and LG.” Now its cultural exports – films like Parasite, shows like Squid Game and bands like all-conquering K-pop arena-sellers BTS and Blackpink, are consumed by audiences worldwide on those phones and in those cars. “K-pop has certainly made people much more aware of Korea, and that success has bled into other areas like film and TV,” says Paquet. Each successful export brings more investment in South Korean art and entertainment, he adds. Squid Game, its most far-reaching cultural export yet, could just turbo-charge investment in (and exports of) South Korean pop culture to the UK and beyond.

A translation industry overhaul

The impact of Squid Game is unlikely to be limited to South Korean shows and films, though. Take a wider glance at the film and TV landscape, and you’ll notice that Squid Game wasn’t alone in bringing subtitled content to the English-speaking masses in 2021. At multiplexes, the recent Marvel movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings became the first pandemic-era movie to surpass $400 million at the global box office, earning $100 million in just five days after its release in the US – despite large parts of the movie being in Mandarin with English subtitles. The movie adaptation of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights musical similarly proved successful with English-speaking audiences, who evidently thought nothing of the fact that its dialogue and lyrics frequently drifted into Spanish as a reflection of the Latinx community the film depicts (and Spielberg’s new version of West Side Story features Spanish dialogues without English subtitles).

There’s a larger trend that it fits into, of audiences raised on the internet not seeing geographic borders the way people once did

This, industry analysts claim, is reflective of a more globalised pop cultural landscape. Turn on your radio in 2021 and you won’t have to wait long to hear artists like Latin pop pioneer Bad Bunny or the aforementioned BTS – both of whom have scaled the charts and sold out arenas in English-speaking markets despite performing in their native languages. “There’s a larger trend that it fits into, of audiences raised on the internet not seeing geographic borders the way people once did,” says another streaming service source, who points out that it’s a development accelerated by platforms like TikTok, where pop culture references and recommendations are shared among its international user base (a “Squid Game dalgona cookie challenge” began trending on TikTok, amassing over 58m views and helping drive the show’s popularity among younger audiences). “In 2022, expect more non-English language content from everywhere breaking through,” they predict.

Already the wheels seem to be in motion on this. Earlier this month, reports emerged of a “translator shortage” as companies who provide subtitling for other markets on movies and TV shows struggle to keep up with the demand created by shows like Squid Game. “Nobody to translate, nobody to dub, nobody to mix – the industry just doesn’t have enough resources to do it,” David Lee – CEO of Iyuno-SDI, one of the industry’s largest subtitling and dubbing providers – told technology site Rest of World as a (surprisingly fascinating) debate erupted online over the way that subtitles find their way onto our screens.

In September, Korean-American influencer Youngmi Mayer made a viral video pointing out inaccuracies in Squid Game’s English translation – moments that lose important cultural context or misrepresent vital pieces of characterisation (although viewers also argued that Squid Game’s translated subtitles were more accurate than the closed captions provided to improve accessibility). These shortcomings arguably could be linked to a labour crisis connected to low pay and high-pressure working conditions: Netflix, as Rest of World points out, pay only “$13 per minute for translation of Korean audio into English subtitles, [with] only a fraction of that figure [ending] up directly in the pockets of translators.” These rates are reflective of industry norms.

The quality of Squid Game’s English subtitles has been questioned by some South Korean viewers (Credit: Netflix)

The success of Squid Game might cause those norms to be improved upon. With Hwang Dong-hyuk’s show proving the commercial potential of non-English language shows crossing over into other markets – Netflix have estimated that Squid Game has generated almost $900m in value for the company – Paquet hopes that things may soon change. “It’s difficult to translate a lot of the nuance of the Korean language in words that flash up so quickly on screen. I do think if you put a lot of time into the subtitles it really does improve the viewer experience. [But to do that you need] more resources and more time budgeted for it.”

The death of remakes

“Just a few years ago, Squid Game would have been something shared within the industry primarily as particularly strong American remake fodder,” influential US film industry figure and founder of screenwriting website The Blacklist Franklin Leonard tweeted recently. A decade ago, Leonard argues, the strong likelihood is that most global viewers’ initial encounter with a show like this would have been with a US-made interpretation of the material. In the early ’00s especially, US retellings of Asian horror films in particular were ever-present in cinemas.

The success of Squid Game could theoretically put the nail in the coffin of this diminishing trend. With Squid Game (and for that matter, Shang-Chi) indicative of a cultural softening of hesitancy towards subtitles, and therefore a desire to watch the original if it’s made available, why go to the bother of reworking it with a British or US cast?

“The case for [remakes] has become more limited,” says Chen. “Take Squid Game. Could there be a remake of Squid Game? Conceivably, but I think many would argue it’d be pretty pointless.” There’s always going to be a case for remakes in situations where people don’t have easy access to the original work, or in which a different cultural context is able to add significantly to the work at hand, he says, pointing to Martin Scorsese’s reinterpretation of Hong Kong mob classic Infernal Affairs, 2006’s The Departed as a good example. “That added significantly on to what was already there by putting it in the new cultural context of the Boston mafia. Where it becomes a different type of story by setting it a new place, I think there’s still value there. But the situation in which it’s useful and financially profitable to remake something is becoming more and more limited.”

The Departed has been praised as a remake that reinterpreted the original to add another dimension (Credit: Alamy)

The jury is out on whether Squid Game will actually represent the beginning of the end for remakes. Curiously, Netflix currently has a Korean remake of Money Heist in production, while Tilda Swinton and Mark Ruffalo were recently in talks to star in a TV spin-off of Parasite, created for streaming service HBO Max, suggesting there’s life in the US remake format yet. Train to Busan director Yeon told Time magazine: “My personal hope is that the new remake will not really refer to or think too much about being loyal to the original work… as the creator, if it was almost exactly interpreted compared to the original work, wouldn’t it be better to just watch the original Train to Busan?”

What is certain, however, is that the central theme in Squid Game will continue to be discussed in films and shows from around the world – whatever the language or country of creation. “Squid Game was about capitalism, the same way that a show like [Jesse Armstrong media mogul drama] Succession is about capitalism,” observes Chen. “Both deal heavily with capitalism and the dangers thereof. In a world that’s grappling with the pandemic, income inequality and healthcare issues have become magnified. There’s a reason why those particular stories have really resonated with people. I’d say that the fact that they both deal with capitalism has been a huge factor in their popularity.”

The ripples created by Squid Game’s success will take some time to be felt but will be fascinating to observe. As Park Hae-soo’s Sang-Woo declares during an intense battle in the show’s final episode: “We’ve come too far to end this now.” The same might be true of Squid Game (the show has been renewed for a second season) – and the influence it will have on film and TV in 2022 and beyond.